4 During and After Class

Now that you’ve prepared for class, let’s discuss what happens during class. If you are reading this before you’ve started law school, some of this may seem a bit daunting. That’s alright, it’s merely meant to give you a preview. You can always come back and use this as a reference as you go through your semester.

Also, note that law school exams might be very different from what you’ve experienced in the past. I mention this, and go into greater detail in the next chapter, because you want to know how you will be tested as you take notes and process information. Law school exams are hypothetical situations or stories. Meaning, that you won’t be asked to merely recite the law or recite facts from cases. Instead, you’ll be asked to apply the law you learn to new situations. With that in mind, let’s dive into class!

I. Cold Calling and the Socratic Method

During law school, many professors will use “The Socratic Method.” Developed by the Greek philosopher, Socrates, the Socratic Method is a dialogue or discussion between professor and students. This means that the professor will ask questions in an effort to explore the subject matter. The reason behind this is so that students are active participants in the discussion, not merely passive observers. The class becomes a dialogue, not a lecture, and the questions are supposed to be thought-provoking. More importantly, this will help you prepare for exams since the Socratic Method allows the professor to explore the subject matter in a new way, using hypothetical situations similar to exams.

All of this is meant to foster active and critical thinking among students. However, it can often prove intimidating, because of “cold calling.” This means that the professor doesn’t wait for a volunteer, but rather, picks someone randomly in class to answer the question. It’s been my experience that this causes a great deal of anxiety for law students, and I completely understand why. It can be incredibly stressful to be called on and put on the spot even if you do know the answer—but even more so if you don’t know the answer.

While I can’t take away the anxiety, or make it less stressful in the moment, I can tell you that no one will mind if you get the answer wrong. Everyone who has been to law school remembers when they were called on for the first time, or the time they were called on to answer a question and had no clue what was happening, or spectacularly messed something up. Every single lawyer has had that experience. However, none of us (or very few of us) remember when our classmate got something wrong. Typically, your classmates are so focused on what they are learning, and honestly, probably being confused as well, that they don’t notice your mistake.

Also, remember that class discussions in general don’t count towards your grade. They may count towards class participation, but that doesn’t mean you lose points if you get an answer wrong. So, don’t hesitate to dive in and participate—it will actually help you learn. Also, as a tip, if you volunteer you are less likely to be “cold-called,” so it’s a win for you and for the class!

Finally, don’t be afraid of talking too much in class. If you have a question, it is more likely than not that someone else in the class has that same question. The professor will make sure that other students have an opportunity to participate in class. Student questions are an integral part of class time, so don’t be afraid to speak up.

II. Taking Notes

Obviously, you want to take notes in class. However, you don’t want to just take dictation, you also want to actively listen and participate in class. By that, I mean that you shouldn’t just write down everything the professor says, or everything that happens in class. You want to be a bit more selective.

a. Handwritten vs. Typed

One big debate about note-taking is whether you should type your notes or handwrite them. Both have pros and cons. There is science that says that you retain more information by handwriting things,1 but that is largely dependent on the situation, and the person. The key thing is to do what works for you! However, I’ll give you some pros and cons of both.

Handwritten notes

Pros:

- Potential to process and remember the information better2

- Less likely to take “dictation” and instead only write about the things that are important (this also helps with processing)

Cons:

- More difficult to organize

- Sometimes harder to keep up

- Can be less neat when you go to reread

Typed Notes

Pros:

- Typically neater

- You can organize as you go

- Can typically type faster

- Can plan ahead a bit better (see below)

Cons:

- It’s tempting to take “dictation” when typing

- Might not be fully processing information

- Might be so focused on typing that you aren’t fully participating in class

Note that some professors ban laptops and audio recorders in class. If you need an accommodation to use a laptop—perhaps you have difficulty writing by hand—please be sure to ask for an accommodation. Sometimes this process is formal, but sometimes you can just ask your professor.

b. Preparing Ahead

To help you avoid just taking dictation, there are things you can do to prepare ahead of time, ensuring that you have less to write during class. This will help you pay attention and be an active participant in class.

First, merely briefing your cases is a good way to prepare your notes ahead of time. If you plan to type, you can also put case headings and facts in your notes ahead of time to save you from having to type them during the discussion. Also, just as you would do with case briefing, you can use your book table of contents to see how things fit together or to help you choose headings. In addition, you can put any statutes or other information in your notes before class.

Some professors may provide their PowerPoints before or during class. You can use these to assist in organizing your notes, or even take notes on the PowerPoints themselves. Also, if you know the professor will make the PowerPoints available, even if it’s after class, you know that you don’t have to copy what is on the PowerPoint to your notes since you can add those later. This will help you avoid taking dictation and allow you to participate in class.

c. What to Take Notes On

I keep saying don’t just take dictation, but really pay attention and actively listen. What do I mean by that? Well, you go to class to gain the information you might not get merely from the reading. Some great things to look out for are:

- Things your professor spends more time on.

- Hypos, or hypothetical examples, that your professor spends time on. Is your professor changing facts in a case? Or asking a lot of “what if this happened instead” questions? Jot that down! And pay attention to the answers. This will help you prepare for your exams since your professor is the one that writes your exams, and the exam question will likely be similar to the in-class hypos.

For more, see the CALI Lesson Note-Taking in Law School 101: The Basics.

And for a slightly more advanced lesson on note-taking: Note-Taking in Law School 101: Case-Based Content.

III. Right After Class

Even after class ends, you still aren’t quite done with class. You might feel exhausted and just want to turn your brain off for a minute, but before you do, take 5 to 10 minutes to look over your notes. Were all of your questions from the reading and briefing phase answered? If not, jot them down—or highlight them—and see if you can chat with a professor or teaching assistant right away. If another class is coming in, or your professor doesn’t stick around, that’s okay—make a note of the specific questions you still have and visit during office hours or make an appointment to chat with your professor.

Now is also the perfect time to do a quick review of your notes and fill in any gaps or clarify things. If you wait too long, you may have forgotten important pieces of information. Doing this for 5 to 10 minutes after each class will save you time in the long run, and help make sure you really understand what happened in class.

IV. Creating Your Outline

In the next chapter, I’ll discuss how you can prepare for your exams. But preparing for exams doesn’t just happen in the days or weeks leading up to the final exam. You can and should start that preparation within the first month of law school. One key way to do this is through the outlining process. The process of building an outline ensures that you stay caught up and continue to understand the material as well as serves as the ultimate study aid at exam time.

a. What is Outlining, or Synthesizing?

You will often hear law students talk about “outlining,” so let’s break down what that means and when you should do it.

First, I’d prefer that everyone switch from calling it outlining, and just call it synthesizing information, as that is what you are doing. In this guide, I use the two terms interchangeably. The point of outlining is to take the information from each class and put it together. It’s the process where you are basically seeing how it all works together. I hate the term “outlining” because most people think of the typical outline with Roman numerals. So, the first thing you should know is that outlining can take any form: from a typical Roman numeral outline, charts, flowcharts, or a mind map3, to, well, anything you want!

So, how should one synthesize? First, you need to know why you are doing it. To do this, we need to skip ahead a bit and talk about final exams. As mentioned above, for your final exam your professor will likely give you a hypothetical to answer—a story, or problem, to solve. We will discuss this in greater detail in the next chapter. But it’s essentially a story, where things go wrong, and the professor wants you to identify and solve the legal problems.

This means that the exam won’t ask you to just restate facts from cases; you have to use the cases you read and compare and contrast them to the new situation. To do that, it helps to “outline” and put it all together.

Each case you read should give you a little more insight into the rule, or law, and how to use it. Think of it as collecting puzzle pieces.

For more information, see the CALI Lesson Outlining Basics.

b. Practice Synthesizing

Outlining or synthesizing can feel strange. You are essentially piecing together available information in order to ascertain the rule. This information will primarily come from cases that you read. Throughout this process, you are also helping yourself to explain or understand the rules you’ve been learning. So, let’s dive into some synthesizing!

First, bear with me as I’m going to use a music example because I’m a huge music nerd. Imagine that you are interested in predicting who might be inducted into the next Rock and Roll Hall of Fame class.

You notice the following inductees:4

|

2021 |

2020 |

2019 |

2018 |

|

Foo Fighters Tina Turner Carole King The Go-Go’s Jay-Z LL Cool J |

Depeche Mode The Doobie Brothers Whitney Houston Nine Inch Nails The Notorious BIG T. Rex |

The Cure Def Leppard Janet Jackson Stevie Knicks Radiohead Roxy Music |

Bon Jovi The Cars Dire Straits The Moody Blues Nina Simone Sister Rosetta Tharpe |

You look at the various lists and try to decide what they have in common and whether you can predict the criteria for being inducted into the Hall of Fame. Maybe you are familiar with the musicians, maybe you aren’t. You do some research on the various musicians; you listen to their music, look at their biographies on the Hall of Fame’s website to get a feel for what they deem important, and so forth. This would be similar to reading cases.

A look at the Hall of Fame’s website gives us some insight, stating:

Leaders in the music industry joined together in 1983 to establish the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame Foundation. One of the Foundation’s many functions is to recognize the contributions of those who have had a significant impact on the evolution, development and perpetuation of rock and roll by inducting them into the Hall of Fame. Artists become eligible for induction 25 years after the release of their first record. Criteria include the influence and significance of the artists’ contributions to the development and perpetuation of rock and roll.5

This is like a statute, which you might use in classes like civil procedure or criminal law. It’s a great starting point. From this description, how would you state the “rule” for getting inducted into the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame?

Interactive Question: Rule Synthesis

Now, this is where my example falls apart just a little, for three reasons: First, music is subjective, and there is always controversy over who is and isn’t included. Second, the Hall of Fame doesn’t release the rationale for inclusion, unlike a judge. Third, I don’t expect you to go read up on all the artists I just mentioned.

However, say you were like me and you were a bit indignant that Rage Against the Machine was not yet inducted, and you wanted to make a case for why they SHOULD be inducted. You’d compare the other artists listed above (or from prior years on the website) to Rage Against the Machine. Again, this is harder with music since it’s subjective, but the law can be frustratingly subjective as well. Essentially, what I just described above is lawyering. Except instead of arguing whether your favorite band should be included, you are arguing whether something is a battery, or whether a claim was filed appropriately—a bit less exciting if you ask me, but also more important in the long run.

Let’s try a slightly different example. What if your client is a homeowner in an area with a set of neighborhood rules? Your client wants to build a firepit, and house that firepit close to their deck. Essentially, the client has a large deck and would like to build the firepit within the deck. Like this:

The applicable rule states: “Any propane, natural gas, wood flame, or gel open flame device must be at least 10 feet away from any structure.”

Your client plans to build the pit 10 feet away from the house, as their deck is quite large, but the question is: Is the fence and bench a structure? Is the deck a structure? How do you advise them?

Step one is to look at the dictionary definition of structure, or whether the neighborhood rules have defined structure. In this example, let’s assume that the neighborhood rules have not defined “structure.” So, our first step is the dictionary:

The dictionary definition isn’t overly useful. It’s likely too broad. We need more assistance. What is the reasoning behind the neighborhood rule? What do other people in the neighborhood have? Let’s say you do your research, and you find this:

“The neighborhood has enacted this rule to prevent the spread of fires. They are concerned that grills, or other flame devices, will pose a fire hazard if too close to a house or garage.”

So, the reasoning is a fire hazard, and the rationale even states “house or garage” instead of structure. Is the deck part of the house? Again, you’d want to look at what the neighborhood has allowed in the past. What they’ve allowed in the past is similar to reading cases.

Hopefully, you are getting the idea. Take some time to go through the CALI Lesson Introduction to Rule Synthesis. In it, the author has you compare and contrast sandwiches, so maybe eat lunch as you work through the lesson!

c. When Do You Start Outlining?

Well, the sooner the better. It’s difficult to start outlining in the first week or two, as you don’t have enough information to synthesize. However, by week three or four, I’d start outlining a little bit each week.

You want to do this for two reasons: First and foremost, it will save you time in the long run and leave you more time to do other things that will help you prepare for final exams. But more importantly, similar to reviewing notes after class, it will alert you to whether you are truly understanding information earlier rather than later.

If you are unable to figure out how to synthesize a section, meaning, you just can’t see how it all fits together, this is a great time to consult your study group (discussed below), a teaching assistant, or your professor. Leaving it to the last possible opportunity, at the end of the semester, means it’s going to be more difficult to put it all together and far more difficult to understand the pieces you are struggling with.

d. Other Outlining Notes

Finally, I want to address some other “tips” that might help you get started in your rule synthesis.

Use your syllabus or TOC!

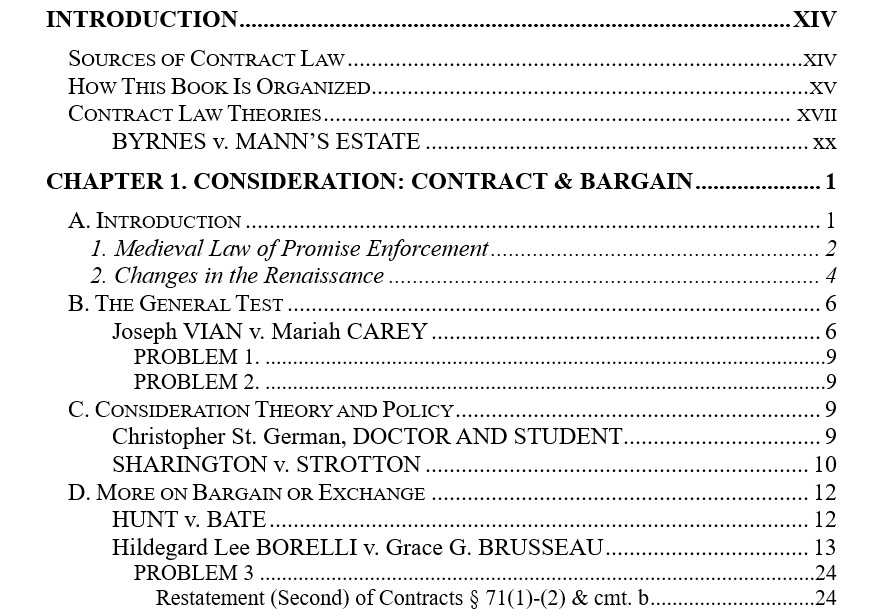

If you are a bit unsure of where to start, or how to start organizing things, look to your syllabus or table of contents. It’s a great way to start to “see” the big picture. For example, let’s look at another casebook’s table of contents, from The Story of Contract Law: Formation by Val Ricks, published by CALI eLangdell® Press.

In this example, you can see a few things. First, similar to how you might use a TOC in your reading, you know that Hunt v. Bate is going to go under the heading of “Bargain or Exchange.” You also know that Restatement 71 is going to go under “Bargain or Exchange” as well. So you at least have a start to your outline.

You can also zoom out, so to speak, and look at the entire table of contents. Advance through the pages below to start to see how these things might work together.

For example, you start with contract formation, and then look to “alternative theories” of recovery, and then look to limits on defenses, or bargains.

If you haven’t started classes yet, this is all going to seem very overwhelming. I suggest you just take it in as food for thought, and then come back after a few classes and read more carefully.

Personally, I used to use my professor’s syllabus as a starting point since that is the way your professor likes things organized. I would then start expanding with things that made sense to me, like charts and mind maps.

Check in often with your outline to determine its effectiveness.

I started most of my outlines with the typical Roman numeral format. And this works most of the time, and for most people. But if it doesn’t work for you, don’t hesitate to shift gears. You might feel like you’ve already “wasted time” spending a few weeks on one type of format, so you can’t possibly change now. First, that’s not wasted time, as you’ve been processing and reviewing material and that will pay off. But most importantly, if that particular format doesn’t work, you have to shift to something that works better for you.

You might also realize that different formats work for different classes. In my mind, contracts class lends itself to Roman numerals and feels very linear. However, with civil procedure, at least in my mind, I need charts and mind maps. Don’t limit yourself. The goal is to understand how to use the information you have in front of you, so don’t be afraid to experiment.

Don’t just use other people’s outlines.

I have two very unwavering beliefs: first, that sharing information is incredibly valuable, and second, that outlines are incredibly personal.

It’s okay to collaborate on outlines and share ideas with your study group and classmates. It’s also okay to look at what upperclassmen have done and what has worked for them. Doing this might help you figure out what outlines can look like.

However, note that the process of creating an outline is the useful part. You can’t just take an outline from a classmate and use that to study. The process of putting things together is what helps you prepare for exams. The whole point of outlining is to help you see the “big picture” of what you are studying, and how things work together. That’s why the work of creating the outline is what is helpful, and just using a prepared outline from someone else is not.

V. Study Groups

As you enter law school or talk to people about law school, many will have opinions on study groups. First, what is a study group? At a very basic level, study groups are small groups of students, about three to six, who do their studying together. Each study group, since they are made up of different people, is going to be set up a bit differently. The idea is that they help each other through reading and briefing the cases, and then compare and share notes after classes. First, we’ll look at some general dos and don’ts of study groups, and then we’ll do some exercises to help you decide whether you want to join one.

a. The Dos and Don’ts of Study Groups

Do…

Compare notes. It’s perfectly acceptable to collaborate and compare notes. The legal profession itself is collaborative. You should still take your own notes, but it might be helpful to share what each of you thought about the class. Maybe someone in the study group picked up something that you did not, and vice versa—help each other fill in the gaps.

Talk through hypotheticals. Your professor might give you practice hypotheticals—see below. You can also find them in various supplements—again, see below. This is what study groups are made for! Talk through them together, and share your thoughts. You can also do this with smaller “hypos.” Often, your professor will ask “what if” during class, just changing a few facts or making up small stories. Write these down in class, and talk through them with your study group.

Don’t…

Divide and conquer. It doesn’t work. Some study groups like to split up the reading or note-taking and then share. For example, if there were four cases to be read for civil procedure, the study group might each read and brief one case and then share their brief with the other members of the group. DO NOT DO THIS. I’m all for sharing, but trust me when I say this will not help you. It might feel like a relief to divide the workload, especially in the beginning; however, you get better at reading and briefing by practice. Not to mention, if you haven’t read the case, the brief might not make sense to you which is going to hamper your ability to follow along and participate in class.

Spend too much time socializing. Hopefully, you like the people in your study group, and if so, this is a great thing. You might make some terrific lifelong friends in law school, and I hope that you do! Because of this, it often happens that “study group” turns into “let’s just talk and socialize.”

Listen, I relate. I’m a super chatty person, and it takes discipline for me not to spend entire committee meetings trying to catch up with colleagues that I legitimately enjoy spending time with. However, that’s not the purpose of the study group (or my committee meeting). Set boundaries for yourself and the group. Something that works very well is setting goals, or timelines, where you can (and should) take breaks and talk, eat together, and generally socialize.

Stay in a group that doesn’t work for you. Maybe you aren’t getting along with your group, or your study habits don’t match up. Maybe you are finding that talking through various things only serves to confuse you, not help. Don’t stick with a group or method that isn’t working. There is no harm in leaving the group, finding a new group, or just flat out deciding that you’d prefer to do this alone.

b.Should I Join a Study Group?

Take a moment now to think about how you’ve studied in the past and what has worked for you. What has been your experience working in groups and working alone? The following tool helps you collect those thoughts and rate the benefits of each approach.

Reflection Exercise: Studying in Groups Versus Alone

Whether a study group is for you is completely a personal decision. There is nothing that says you must join a study group, and that is fine. However, the law is often collaborative and it can help to talk things out or work through hypotheticals as a group. So, my advice is, even if you don’t have an official study group, find one to two fellow students that you can meet with a couple of times throughout the semester—specifically before midterms and finals—and talk through problems, questions, etc.

Remember, there is no “right” way to do things, so if you want to join a study group, find a group of people who have similar goals and needs to you. You can always join a study group and later decide it doesn’t work for you, or join a study group late in the semester.

If you’re considering joining a study group, or are already part of one, use the following exercise to work through (a) what you need from a study group; and (b) if you’re already part of one, whether or not that study group is meeting your expectations.

Reflection Exercise: Study Group Goals

For more information, see the CALI Lesson Study Groups: Best Practices.

VI. When to Ask For Help

Don’t wait until just before the final exam to decide that you are a bit lost. The better option is to ask for help as soon as you are feeling lost. The problem is, how do you know if you are lost?

If your professor gives you quizzes or any practice hypotheticals, how are you feeling about them? If you get feedback from your professors, is it good? Even if it’s only the first quiz, if you are scoring below the average in the class, go see your professor. Similarly, if you have a practice midterm, even if the feedback is good, go see your professor—what could you have done to do better?

What if you don’t get feedback? You can still do practice hypos—how do you feel about them? Do they make sense to you? Is your answer matching the sample one, if there is one?

You can also do CALI Lessons, in almost any subject! How are you doing on those? If the answer is not great, that’s okay, and normal! But it might be a signal to ask for help.

Asking for help is something you should do. I have so many students who either wait until it’s too late or never come for help at all. Why? They’re embarrassed. Or, they think they can figure it out on their own. Your professors, and your academic support professionals if your school has some, very much want to help you. You might also have tutors or teaching assistants that want to help you. We are all invested in your success, and I mean that sincerely. So, even if you aren’t positive you need help, seek it out.

VII. How Can a Professor Help Me? (And How to Approach a Professor For Help)

Your professors are going to be a great source of help, and most of them will want to help. Professors get excited when you succeed and typically teach because they enjoy it. So, how can a professor help you and when and how should you approach the professor?

First and foremost, professors are the best people to go to if you are struggling with the substance of the class. If you don’t understand something from class or a case you read, go to the professor.

As for timing, sometimes you can approach a professor directly after class. However, if you do this, be aware that the professor might have to rush to go elsewhere, or another class might be coming in to use the room. Be respectful of both of these things. The after-class discussions are best used for very quick questions.

For much longer questions or times when you want to have a deeper discussion, office hours are best. All professors have office hours and will post the date and time on the syllabus. This generally means that if an office hour is on Wednesday from 2:00 to 3:00, you can stop by the professor’s office at 2:15 without a prior appointment. This is encouraged! The only thing to be aware of is that other students might have the same idea, so you might have to wait.

For most professors, you can also email them and make an appointment. That way you know they will have time reserved just for you.

So, now that you have decided when to go see your professor, what types of questions might you ask?

Questions about cases: Perhaps there was something about one particular case you don’t understand. You feel like you missed the holding, or are not clear on the issue they were trying to solve. Ask your professor!

Questions about something mentioned in class: Your professor is likely to mention “hypotheticals” in class, such as “What if Sally did x, and then Bob did y?” If you don’t understand the answer, ask your professor. Similarly, your professor might take a case you are reading and say things like “What if we changed this one fact?” If you are feeling a bit confused about what it all means, ask your professor.

Questions about how it all fits together: This is valid. Chances are, your professor likes talking about the subject they are teaching and is happy to talk about the big picture or how various concepts might fit together. So ask them! I would suggest that you have thought about it before asking them. For example, you can approach the professor and say “It seems like concept A relates to concept B this way…” and the professor will either agree, or correct you. Either way, you’ve started a great discussion.

What NOT to ask: Don’t approach the professor and just say “I don’t understand torts,” or “I don’t get any of intentional torts.” It might feel like these are valid questions, and trust me, I relate. However, your professor is spending an entire semester lecturing on torts, so you have to narrow it down just a bit.

Don’t ask things like “What do I need for the exam?” or “Will this be on the exam?” The professor’s goal is to teach you how to think like a lawyer and how to learn how to do that using torts, or civil procedure, or contracts. The exam is important, but that shouldn’t be your only focus.

Finally, professors are humans. I promise. We make mistakes; we understand that you make mistakes as well. We won’t judge you for coming in with a less than perfect question, nor will we think you asked the wrong thing. My guidelines are to help you get the most out of your time with your professor, but you should not be worried about asking the “wrong” thing during office hours. Take a chance, and go ask!

VIII. A Note on Supplements

Supplements in the law school context are study aids that come from somewhere other than your professor or class materials. I have a love and hate relationship with supplements. They can serve a purpose, and often be helpful; however, even well-meaning students can often use them as a bit of a crutch, and it’s easy to get overwhelmed and think you need ALL of the supplements. Not only will this cost far too much, but you can’t possibly read them all—it will only get confusing.

There are too many products available and on the market to list or evaluate them all—from commercial products for sale to free sources online to memberships your school provides—so I’ll focus more generally on what to look for (and what to avoid) in a supplement.

a. Choosing the Right Supplements

Good supplements are those that help you work on practice questions and think through the law. Bad supplements are those that do the work for you and only provide you with black letter law or a “canned” brief or outline. Resist the urge to use these, as the work of writing a brief and outline is what is important, not to mention the fact that the canned brief or canned outline might not be suitable for your professor.

Some good supplements I recommend to students are CALI, Examples and Explanations, Glannon Guides, and anything that makes the student an active participant. The reason I recommend these is because they all contain questions and sample answers, which helps you with active learning.

b. Some Dos and Don’ts of Supplements

Do find out what your professor recommends, or talk to students that have had that professor. Some professors have preferences, and might even use those supplement questions as parts of their exam. So, if a professor has a preference, definitely use it. Conversely, if your professor says they hate supplements or don’t think they are necessary, you might want to avoid them for that class if you are able.

Do use them to practice and test your knowledge. The supplements I recommend all have different types of questions, from essays to short answers to multiple-choice questions. These are the best kind of supplements, as they literally “supplement” your in-class learning.

Do NOT rely on supplements in place of reading and briefing cases or outlining yourself. They should be supplementing your work, not taking the place of it. For example, if you rely on an outline someone else made, it might not fit your class or your learning style, and most importantly, making the outline yourself helps you process the information!

For more, see the CALI Lesson Creating Study Aids.