2 But I Already Know How to Study!

I. Introduction

You might already be wondering why there are so many chapters on studying. I mean, you made it to graduate school, certainly you know how to study, right? Sure, but studying for law school is very different. We’re going to talk about why.

The biggest reason for the difference is that you are not learning facts or figures, but rather, you are learning a new skill: how to think like a lawyer. As I mentioned in Chapter 1, learning the law is a skill. For some reason, this isn’t obvious to most law students, or many practitioners. It’s viewed as a lofty intellectual pursuit, where people can have very robust intellectual conversations about various aspects of the law. And sometimes it is, I suppose. But mostly, it’s a skill. And in your first year of law school, and sometimes your second and third years, you have to remember you are learning a NEW skill and learning to master something you’ve never done before.

I present to you, by way of an example, how I learned to roll a cake:

See, I’ve been baking since I was a little girl. I started baking with my grandpa, learning to make banana bread, brownies, and cakes. I bring this up because I don’t consider myself a baking novice. I’m not an expert, but I thought I had skills. So, when my British husband declared that he really missed yule logs (which can be purchased in the US, but the store-bought kind is never the same I guess) I leaped at the challenge to master a new baking skill.

I first watched about three videos on “how to roll a cake.” I learned that you: 1) use a jelly roll pan (thinner pan, like a cookie sheet); 2) put the cake on a towel RIGHT AWAY; 3) roll it; 4) unroll it; 5) frost it; and finally 6) roll the cake again. I used my normal chocolate cake recipe and got to work. You see, I’ve baked cakes so many times before, and I really like my recipe. I’m comfortable with it, too. I was excited and whipped it up just like I always do. I baked the cake. I put it on the towel and rolled it. I set the roll aside to let it cool. I felt pretty pleased—all seemed to be going well—and I was excited to unroll and frost it. But, as I unrolled it, it came apart in pieces. Delicious pieces that I ate—I’m not a fool—but it wasn’t supposed to unroll in pieces.

The next day I decided to try again. After all, it’s what one does. I asked the internet for more advice and watched a few different videos to see if I could learn anything new. The only thing I picked up was that I may have rolled it while it was TOO hot. So I did everything the same but waited until it was warm instead of hot. Rolled it again. This time it came out in FEWER pieces, but pieces just the same. My husband and I were delighted to eat the mess, but I kept pondering what I needed to do to roll this cake.

I’m not going to lie, I was frustrated. True, I was enjoying the delicious cake, but it was still frustrating to not get the results I wanted.

So, instead of just watching videos on the actual rolling of the cake, I opted to go look at some yule log, swiss roll, or roulade (all rolled cake) recipes. I noticed something strange: the recipes were not like my recipe at all. The ingredients were vastly different. I picked a yule log cake recipe and tried again. This time it worked! The different recipe meant a different cake consistency, so a better roll!

Why does this matter? Why is this like studying the law? Well, first and foremost, I went with a preconceived notion of what I knew and what I could do. It took two attempts before looking back and thinking that I might need to change my initial recipe. But that made all the difference. Often, students come in with a preconceived notion of what they know, how to study, or even how to write. They are often shocked to find out that legal writing is vastly different from what they did prior to law school, or even what they considered “good.” The same can be said for study habits. Remember, my sheet cake recipe is delicious, and undisputedly so, but it didn’t work for what I wanted to do, which is to roll the cake. That doesn’t mean that it doesn’t make a great sheet cake, it just doesn’t work in THIS context. The same is true of your writing and studying: your prior writing skills and study skills may be great, and work for some things, but perhaps not law school. You may also have other legal experience—maybe you took a constitutional law or business law class in your undergraduate years, or worked as a paralegal. But that information might not work in THIS context. And all of that is okay! It’s more than okay—it’s why you are in law school.

But why do I bring up this analogy? Because it was frustrating. It was frustrating to fail and not bake in the “correct” way because I view myself as a good baker. It turned out my mindset was vitally important; I AM a good baker, but I had to be willing to learn a new skill, or a new recipe, in this particular context. You are likely a good student and are good at studying, but you have to be willing to learn new skills in this context. Practicing, and learning from your mistakes, is key to honing that skill.

Also, I’m not the only one that loves a good baking analogy!

“I analogize my experience as a first-generation law student to being asked to bake a very elaborate cake without a recipe or ingredients. My first several weeks of law school I looked around at my classmates and felt sure that while we were all expected to bake the same cake, they had both the recipe and the necessary ingredients to do so, while I was lacking both. For them, it would simply be a matter of execution, while for me it would mean figuring out what this “cake” even was and, assuming I could do that without any sense of what it was supposed to look like, where in the heck could I get the ingredients to make it. Of course, the truth was that I was not the only first-generation student in my law school class who felt this way, but what we know call “imposter syndrome” kept us from sharing our fear and uncertainty with each other, so we each set out to bake our cakes alone. My story is ultimately a happy one. Through a lot of hard work, support from understanding faculty and staff mentors, and my innate stubbornness, I did discover the recipe, gather my ingredients, and bake my cake. It was by no means a perfect cake. My baking process was longer and more painful than many of my classmates who came to law school with more educational experience and familial stability than I did, but I suspect that very few of them were as proud of their end product as I was.”

-Professor Sam Panarella

II. Lawyering, and Law School, as a Skill

As I’ve noted, learning the law is a brand-new skill that takes practice. Many students who have previously done well struggle in their first semester of law school and get very frustrated. That is perfectly normal. But think back to learning any new skill—riding a bike, knitting, playing an instrument, even walking—they all took practice.

Throughout this book, I am going to address the various ways that law school is a brand-new skill, or rather, how to perfect those skills. But it is important to give yourself some grace and focus on small improvements.

Think about someone learning to play the piano for the first time. They start small, with a simple song. They master something with a few notes, maybe even starting with just one hand. They aren’t concert-ready in the first week. They are also going to make many mistakes as they learn. In fact, even professional concert pianists are going to make mistakes as they learn new pieces. The key is to learn from each mistake.

So, as you go through your first semester, learn from each mistake and give yourself the grace to make mistakes. I see too many students that think that if they aren’t “getting it” right away there is something wrong with them. I promise you that there isn’t. Learning the law is a skill that is developed over months and years, and is exactly why you are here!

So what IS that new skill you are learning? You may have heard that law school teaches you to “think like a lawyer,” but very few people can tell you what that entails, or even what “thinking like a lawyer” means. But they tell you over and over that you need to learn how to do it.

Well, to put it simply, “thinking like a lawyer” means rules-based reasoning. This essentially means that everything must start with a rule, or the law. In addition, it means that lawyers use analogical reasoning, which is any type of thinking that relies upon an analogy. Essentially, this is the skill you will need to use on all of your exams.

And you DO need to learn how to do it. But how?

First, you need to understand that an analogical argument is “an explicit representation of a form of analogical reasoning that cites accepted similarities between two systems to support the conclusion that some further similarity exists.”1 What does this mean? Well, it means that lawyers compare and contrast things.

For example, people always say “you can’t compare apples and oranges,” but in fact, you can compare apples and oranges.

Interactive Question: Comparing Apples and Oranges

The other part of this thinking is something called the “Gestalt Switch.”

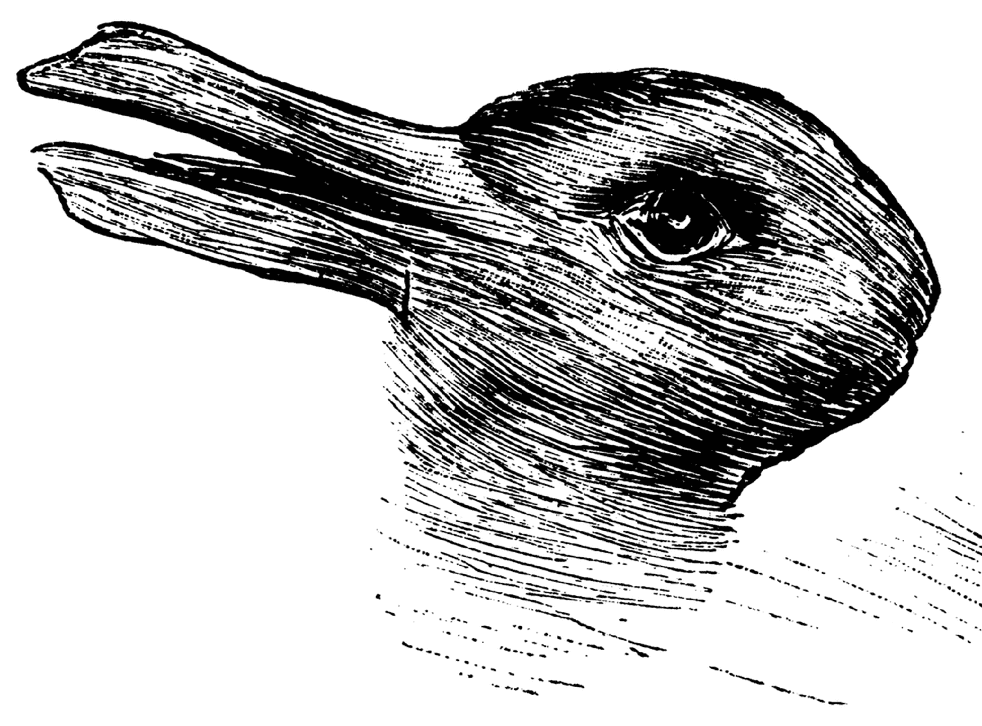

Take a look at this picture:

Most people either see a duck or a rabbit. Depending on which you saw, try to describe to someone else how they might find that animal. For example, if you know that I only saw a rabbit, and you see a duck, tell me how to see the duck:

Interactive Question: The Gestalt Switch

When you can see both photos, and explain both photos, that is called the “Gestalt Switch” and that is what lawyers regularly do. Lawyers have to see both sides of the situation and then be able to explain both sides. In doing this, they usually start with a rule and then explain why the rule may, or may not, apply.

For example, how does one define a sandwich, and where might you go to look for a definition? Suppose someone asked you whether a hotdog was a sandwich. You might laugh and answer yes or no based solely on your gut response. However, lawyers need to first ask, “Well, what makes a sandwich a sandwich?” and base their answer on that definition. They can’t just say “I don’t think a hot dog is a sandwich because I said so”—they have to base that answer on a rule and explain their reasoning.

Maybe we find out, based on restaurant reviews, that sandwiches tend to be meat, and or cheese, with various condiments or vegetables, put between bread. Well, based on that definition, it sounds like a hotdog is very much a sandwich. But it gets trickier when we realize that there are exceptions and you can have sandwiches without meat or cheese! What then?

I realize this sounds complicated, but this is “thinking like a lawyer” distilled down. Don’t worry, it will get easier as you go, and it will become more natural as well. It just takes practice. I wrote a CALI Lesson that can help: Analysis 1: Thinking Like a Lawyer. One of the reasons I urge you to learn, and practice, thinking like a lawyer is because it’s what you will need to do on your law school final exams.

III. Grit and Growth Mindset, and Why They Are So Very Important!

The secret to success in law school is the same as learning any other skill: practice. But to practice, and to learn from that practice, takes a great deal of grit and an attitude that embraces a growth mindset.

Most experts accept that having both grit and a growth mindset is important, and are perhaps THE most important factors in success; not just in law school, but in most areas where “success” can be measured. The following is from the Law School Academic Support Blog:

Grit is defined, by the Merriam-Webster dictionary, as “firmness of mind or spirit, unyielding courage in the face of hardship.” Growth mindset is a frame of mind, a belief system we adopt to process incoming information. People with a growth mindset look at challenges and change as a motivator to increase effort and learning. Most experts agree that grit and growth mindset are the most important factors in success.2

According to Angela Duckworth, author of Grit: The Power of Passion and Perseverance, grit is the most important factor in success. That same Law School Academic Support Blog article goes on to say:

Angela Duckworth is a professor of psychology at the University of Pennsylvania, and founder and CEO of Character Lab. She started studying why certain people succeed, and others don’t. She began at West Point Military Academy, studying why some complete the “Beast Barracks”, essentially a boot camp, while others drop out. Given that to get into West Point, there was a certain similarity of background, in term of grades, extracurricular, etc. she set out to see if she could predict who would make it, and who wouldn’t. It turns out they couldn’t predict this based on grades, or background, but could base it on a grit scale that Prof. Duckworth created. The grittier the West Point cadet, the more likely they would complete the “Beast Barracks”. She later expanded on her studies and found that the grittier you were, the more likely you were to complete a graduate degree. She further expanded this to other professions, Olympians, etc, and found that generally, the more grit you had, the more like you were to succeed.3

Since you are in law school, it will benefit you to look at what grit is, and why it factors into success. The good news is that you can learn to be grittier!

Professor Duckworth devotes an entire chapter to being “distracted by talent.” Meaning we, as a society, tend to see successful people or students and think “They are so talented,” as if what they were doing was effortless. In fact, we don’t see the hard work and the long hours they put in. She uses Michael Phelps, swimmer and multiple Olympic gold medalist, as an example. People see him swim during the Olympics and think “Oh, what talent.” But what they don’t see, what they gloss over, is the time spent in the pool—the hours upon hours of practice, of setbacks, of learning from mistakes.

Similarly, as a law student, you may see classmates answer questions in class and think “Wow they’re really smart,” but you aren’t seeing the hard work they put in. Nor are you seeing the setbacks, mistakes, and wrong answers. For your own mental health, it’s important to remind yourself that what looks like talent is usually hard work.

Professor Duckworth believes that the focus on talent distracts us from effort, which is more important to success. I would argue that not only is she correct, but this tendency to focus on talent causes law students to become frustrated or lose confidence when they feel they are not a “natural.” One of the underlying secrets of law school is that no one is a “natural”! The unique demands of law school are new for everyone. If you are looking at classmates and thinking “This is so easy for them,” don’t be fooled—there is a learning curve for everyone!

The important thing is to realize that your hard work and effort are far more important than any natural ability and to focus on that during law school. Do not get discouraged when you feel that things don’t click right away, or come “naturally.” If your first law school feedback is negative, don’t assume that you aren’t talented or smart enough to be there—remember that everyone is facing the same learning curve and the same challenges. You’ve most likely heard that to become an expert, you must spend 10,000 hours in practice. This is true for the practice of law as well. Even when you graduate, and pass the bar, you are not an “expert” until you’ve been practicing for quite some time. You are not trying to be an “expert” during law school; rather, you are putting yourself on the path to expertise.

Practicing does make it easier, which in turn makes you feel more talented. Basically, to do anything well, you must overextend yourself. During law school, it might already feel like you are overextended in terms of work. But that’s not precisely what I mean. By overextending, I mean you have to do difficult things; things that don’t automatically come naturally to you. This is grit.

According to Professor Duckworth, grit is about working on something you feel so passionately about that you’re willing to stay loyal to it. It’s not just falling in love, it’s STAYING in love. So, you are probably in law school because you want to be a lawyer, and that has been a dream of yours for a while. All of you have different reasons for coming to law school, and you might have taken different paths to get here.

Since grit is about loving what you are doing, or in this case studying, and falling in love with it over and over again, think about why you went to law school and what you want to do with your degree. Law school is hard, and studying is hard, so when you are feeling that challenge and pressure, you want to remember why you wanted to go to law school, what you love about it, and what you want your career to look like. You don’t have to love every subject, and you won’t love every subject, but pick a few things about studying the law that really appeal to you.

Write a letter to yourself to save, whether it’s in a Word document or a notebook or on your phone, so that when you need to fall in love again with why you went to law school, you can.

In addition to grit, you also have to understand what Dr. Carol Dweck refers to as a “fixed mindset” and cultivate what she coined as a “growth mindset.” Someone with a fixed mindset means you think intelligence and talent are innate, unchangeable traits, whereas someone with a growth mindset believes you can develop these things with practice. Don’t worry if you tend towards a more fixed mindset. Despite the name, you can change a fixed mindset, and learn how to embrace a growth mindset.

Professor Dweck explains the negative impacts of a fixed mindset on someone’s capacity to learn:

Believing that your qualities are carved in stone creates an urgency to prove yourself over and over. If you have only a certain amount of intelligence, a certain personality, and a certain moral character, well then you’d better prove that you have a healthy dose of them. It simply wouldn’t do to look or feel deficient in these most basic characteristics.

I’ve seen so many people with this one consuming goal of proving themselves in [a learning setting], in their careers, and in their relationships. Every situation calls for a confirmation of their intelligence, personality, or character. Every situation is evaluated: Will I succeed or fail? Will I look smart or dumb? Will I be accepted or rejected? Will I feel like a winner or a loser?

But when you start viewing things as mutable, the situation gives way to the bigger picture.

This growth mindset is based on the belief that your basic qualities are things you can cultivate through your efforts. Although people may differ in every which way in their initial talents and aptitudes, interests, or temperaments, everyone can change and grow through application and experience.

This is important because it can actually change what you strive for and what you see as success. By changing the definition, significance, and impact of failure, you change the deepest meaning of effort.4

In short, if you focus on learning for learning’s sake, and not the end result like grades, you will get more out of your effort!

Your mindset can change depending on what the task or subject is. Most people don’t have a fixed mindset on everything, nor do they have a growth mindset on all things. For example, if you met me in real life, you’d know that I was tone-deaf. Being tone deaf did not stop me from being in a marching band for four years of high school. I even managed to play the saxophone AND percussion! This, for someone that “isn’t supposed to be good at music.”

In contrast, I’ve always assumed I’m just “naturally” bad at science. As a result, I’ve never really made an effort to get better at science.

Different types of mindsets might interact with grit. For example, I loved playing piano, despite how difficult it could be, but never developed any such love of math. This meant that with the piano I had more “grit,” which led to a growth mindset about learning, and then, in turn, led to success in the way of piano trophies!

Find out how “growth” or “fixed” mindset you are here.5

Reflection Exercise: Growth Mindset

a. Succeeding Through Failure

Failure is part of the learning process. However, failure is hard, and to be honest, we don’t talk about it enough. That’s on us, as lawyers and educators. Society doesn’t allow us to be as forthcoming about failure as we should. It is impossible to have success without failure. Mistakes lead to success.

Each failure is an opportunity to learn and improve. This is not a series of mere platitudes—it is science. For example, Wayne Gretzky is nicknamed “The Great One.” His career stats prove him to be one of the best hockey players ever. So, by all accounts, we would consider him successful. He has four Stanley Cups, 61 NHL Records, a Wikipedia article for JUST his career achievements, and a freeway in Canada named after him. Let’s break those stats down: He spent 20 years in the NHL and earned 894 goals. That’s impressive. But to get to 894 goals, he had to take 5,088 shots on goal. That’s a 17.6% success rate. I would never malign The Great One, but that means he missed 4,194 of those shots. Each shot missed was a failure. But each shot missed was an opportunity for Gretzky to learn and get better. Those career stats do not include his non-NHL years—in some of his earlier seasons, he scored 0 goals. In his first season with the NHL, he scored 51 goals. But he scored 92 in his 3rd season—that’s almost double. I can promise you he was learning from each failure and from each shot on goal that didn’t make it into the net. I know he learned from his failures because he was a wise man, and he is quoted as saying “You miss 100 percent of the shots you never take.” This means the man knew about growth mindset!

That’s enough of my sports analogy, and you can replace Wayne Gretzky with your favorite athlete, favorite actor (ask how many auditions they had to fail before getting their big break, or how many movies flopped), favorite politician, etc. Or, better yet, talk to your law professors or lawyers you admire and ask them how many times they failed.

The important takeaway is that to embrace a growth mindset, you have to view failure as an opportunity to learn and improve.

This may seem counterintuitive when I’m encouraging you to be resilient and grow. However, it’s important to know you CAN fail. Or rather, you can SURVIVE failure. Imagine failing at your next project, and think about what that failure means; what is the worst that can happen? What will it feel like? What next steps will you take?

Generally, it’s good to move forward with a positive mindset. However, knowing that you can come back from failure, and having a plan on how to do it, will help increase the likelihood that you will take more chances. Taking more chances increases the likelihood of success. Let’s work through an example of creating a plan.

Reflection Exercise: Succeeding Through Failure

The best way to learn from failure, or get used to learning from failure, is to take risks. This goes along with pushing yourself out of your comfort zone. For law school, this might mean things like doing practice hypotheticals before you feel 100% “ready,” or getting feedback from professors even if you are nervous about showing off a draft of something.

As you move along in your law school career, this might mean joining things that might otherwise seem daunting, such as moot court or law review. These risks will pay off because they will allow you to learn more about lawyering, which should be your ultimate goal.

So, let’s put into practice everything we’ve been talking about. Write down something, on a sticky or in your phone, that you’ve been afraid to do but want to try. Keep that note with you until you complete it!

b. Forget Perfection

There is a saying among writers, which is “done is better than perfect.” While the law is a career where things like attention to detail are important, if you become too obsessed with perfection, you won’t complete the things you need to. For example, striving for perfection in legal writing might mean that you skip turning in drafts where you can get feedback. On exams, the idea of perfection might keep you from moving on to the next question, or paying attention to time constraints. This happens in practice as well, where lawyers get so focused on the “perfect” memo or “perfect” complaint that it interferes with productivity, or worse, their client’s best interests. Yes, having a good quality work product is important, but perfection is an impossible standard.

It is also important to note that right now, as you are a law student, you are not meant to be perfect. You are meant to be trying and learning and improving.

As I mentioned before, practice DOES make perfect er… success. That’s the entire idea behind grit. If you keep practicing, and learning from each practice, you are on your way to success. This also means not giving up. It’s tempting, especially in the early stages of learning any new skill, to throw in the towel when you get frustrated. A key element of grit is persevering when you feel that temptation to quit. Resisting the temptation to give up can be difficult. To help, think of a mantra to tell yourself in those moments. Put it on a notecard or sticky note, and put it on your computer or mirror.

Remember, if you view “failure” as a learning process, your mindset shifts. Each time you feel frustrated, or feel like you haven’t performed as well as you had hoped, remind yourself that you are still learning.

In this chapter, we’ve been discussing how important it is to practice to improve a skill. If you’d like to “practice” and review grit and growth mindset, check out the CALI Lesson Grit, Growth, and Why it Matters. Or, how to be gritty!

This is all going to be very different, and challenging. But you CAN do it. And in fact, being a first-generation student can absolutely work as an advantage:

“I’ve talked a lot about the challenges first-gen students face in law school and in the legal profession because, frankly, I’ve had to overcome almost all of them with varying degrees of embarrassment, shame, and feeling like I’ve had one hand tied behind my back sometimes. But there is one thing I don’t talk enough about and it’s this: Being a first-gen law student (and later a first-gen lawyer) gives you an enormous advantage and that’s grit. Yes, that’s a popular buzz word these days but the secret is that us first-gens have had this on lock since the moment we walked through those law school doors. We’re plucky, diverse, hard-working, and we know what it means to earn our triumphs. Figuring things out on our own just comes naturally because that’s what we’ve always done. We haven’t met a road block we can’t climb over, swerve around, or crawl under. Grittiness is to first-gens what privilege is to those whose families were able to smooth their way with prior experience, and it is a real superpower in this profession. You’ll be tested in every possible way in law school and in the legal profession and guess what? You’ll be ready. Because you always have been.”

-Professor Ashley London